March 2011

A few years ago, a draft of my first novel received a sweeping round of rejections, all complimentary yet unyielding, a devastating combination. After that, I could no longer look at the document titled "novel" that I'd virtually lived inside for three years. I couldn't imagine writing again without getting a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach that's probably familiar to most writers at some point in their careers.

I couldn't talk about writing without invoking the ultimate futility of life. And, for the first time I could remember, no work of fiction gave me solace. I'm not proud of this, but every time I picked up a novel, all I could contemplate was the plain fact that it was what my own wasn't: published.

Then I stumbled upon a copy of The Writing Life by Annie Dillard. It had been assigned to me in graduate school, back when I was too engrossed in my writing to read it. Now, when I opened the slender, yellowed volume, it seemed to have been written for me at this precise moment.

When you write, you lay out a line of words. The line of words is a miner's pick, a woodcarver's gouge, a surgeon's probe. You wield it, and it digs a path you follow. Soon you find yourself deep in new territory. Is it a dead end, or have you located the real subject? You will know tomorrow, or this time next year.

Dillard goes on to describe the writer's task as that of an inchworm climbing a blade of grass; as "cranking the flywheel that turns the gears that spin the belt in the engine of belief that keeps you and your desk in midair"; as alligator wrestling and lion taming; as "life at its most free"; as the sensation, at its best, of "unmerited grace."

She captured so precisely the place of writing in my own life that, beneath my cloud of self-pity and self-doubt, I knew I needed to write again. Not that day, or that week, or even that month, but soon. And not in agonized pursuit of a book deal, but to see my characters through their journeys by digging a path the only way I knew how: a line of words.

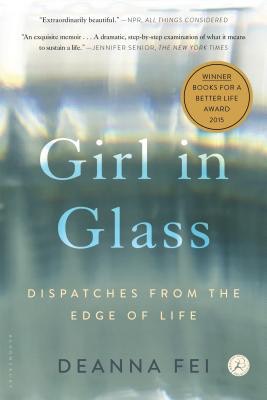

My story has a happy ending in that, after another year or so of writing and revising, hundreds of discarded pages, a falling-out with my agent, a dozen queries to prospective agents, and who can remember what else, my novel was published -- in hardcover last year and in paperback this week. Still, what gives me infinitely more satisfaction than seeing my novel as a finished product -- though I couldn't have imagined this a few years back -- is my own knowledge that I was true to the process.

I would like to think I would've arrived here under any circumstance, but the truth is, we're all liable to lose our way on this uncertain journey. So I thought it might be a worthwhile project to comb my bookshelves and poll writer friends to compile this list of books on writing that have guided us in the right direction at the right time.

First, a few caveats. There are no guarantees in writing -- and certainly not from any book on writing. As Elisa Albert, author of The Book of Dahlia and How This Night Is Different, cautions, the best way to learn how to write is by "reading and rereading good books" -- not only books on writing, of course. And (this always bears repeating, even to myself) to write: every day, at the center of your life.

And yes, the entire enterprise of writers recommending books about writing by other writers might seem self-indulgent and self-regarding, another illustration of how badly us literary types need to get out more. Trust me, we castigate ourselves for that all the time -- and question our purpose on this earth. For the obverse of the freedom one finds in the writing life is the sense that, to quote Dillard again:

Your work is so meaningless, so fully for yourself alone, and so worthless to the world, that no one except you cares whether you do it well, or ever... Your manuscript, on which you lavish such care, has no needs or wishes; it knows you not. Nor does anyone need your manuscript; everyone needs shoes more. There are many manuscripts already -- worthy ones, most edifying and moving ones, intelligent and powerful ones... Why not shoot yourself, actually, rather than finish one more excellent manuscript on which to gag the world?

Though we might not always have the answer -- and though our manuscripts might be far from excellent at the moment -- sometimes all we need to know is that writers wiser than ourselves have asked themselves the same question.

Here, in no particular order, are seven books on writing for every writer.

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

I've stopped clutching this book like a security blanket, but I still like to keep it close -- for practical comfort ("It takes years to write a book -- between two and ten years... Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks... Some people feel no pain in childbirth. Some people eat cars. There is no call to take human extremes as norms"), for inspiring exhortations ("Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case"), and for the poetry on every page.

Dreaming by the Book by Elaine Scarry

When I was a student at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, Frank Conroy strode into the classroom one afternoon and, instead of launching into a critique of that week's story, handed each of us a copy of this book. After I delved into it (it does require delving), I understood why. It's a truly unique synthesis of literary criticism, philosophy, and cognitive psychology that illuminates the particular challenges of the literary arts, which, "unlike painting, music, sculpture, theater, and film -- are almost wholly devoid of actual sensory content" -- and that details precisely how great writers work the miracle of evoking images more vivid than our own daydreams.

The Art of Fiction by John Gardner

Gardner's stern edicts on such aspects of craft as psychic distance, sentence rhythm, the structural units of a novel -- and how to avoid sins ranging from accidental rhyme to sentimentality -- are enough to shake the dreamiest writer out of complacency, all under the imperative of maintaining the only dream that matters, "the vivid and continuous fictional dream" that a writer creates for a reader.

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

Kate Levin, a contributor to Fiction Writers Review and the Nation, speaks for many when she says, "I first read Bird by Bird during my first year of college, and it was revelatory to me to read a book on writing that was so unpretentious, funny, and wise. She seemed to speak to my exact anxieties about writing, and in doing so helped me to understand that this is just the stuff one has to go through to get the words down on the page. I return to the lessons of her 'Shitty First Drafts' section again and again." I also love Lamott's description of what it feels like the day your book comes out -- essentially, visions of lush bouquets and blaring trumpets collapsing into one phone call, if you're lucky.

Story by Robert McKee

Most of us who come through writing workshops hone our craft on short stories and find ourselves bewildered when we attempt to tackle our first novel, a form that, in many ways, is more akin to film, particularly in terms of scope, structure, and plotting. That's where this bible of screenwriting has much wisdom to offer, starting with McKee's first principle: "Anxious, inexperienced writers obey rules. Rebellious, unschooled writers break rules. Artists master the form."

Mysteries and Manners by Flannery O'Connor

Jon Tribble, managing editor of the Crab Orchard Review, cites this as one of his favorite quotes from O'Connor:

There is one myth about writers that I have always felt was particularly pernicious and untruthful -- the myth of the "lonely writer"... supposedly, the writer exists in a state of sensitivity which cuts him off, or raises him above, or casts him below the community around him... Probably any of the arts that are not performed in a chorus-line are going to come in for a certain amount of romanticizing, but it seems to me particularly bad to do this to writers and especially fiction writers, because fiction writers engage in the homeliest, and most concrete, and most unromanticizable of all arts... Unless the novelist has gone utterly out of his mind, his aim is still communication, and communication suggests talking inside a community.

Personally, I love that inimitable, cranky brilliance of O'Connor's in sections like this:

People have a habit of saying, "What is the theme of your story?" and they expect you to give them a statement: "The theme of my story is the economic pressure of the machine on the middle class" -- or some such absurdity. And when they've got a statement like that, they go off happy and feel it is no longer necessary to read the story.... But for the fiction writer himself the whole story is the meaning, because it is an experience, not an abstraction.

Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

Thrity Umrigar, author of The Space Between Us and The Weight of Heaven, puts her love for this book very simply: "I love the passion in it and the intensity of the language." Here's a sample: "Try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books written in a foreign language. Do not now look for the answers. They cannot now be given to you because you could not live them. It is a question of experiencing everything. At present you need to live the question."